Persistence Learning

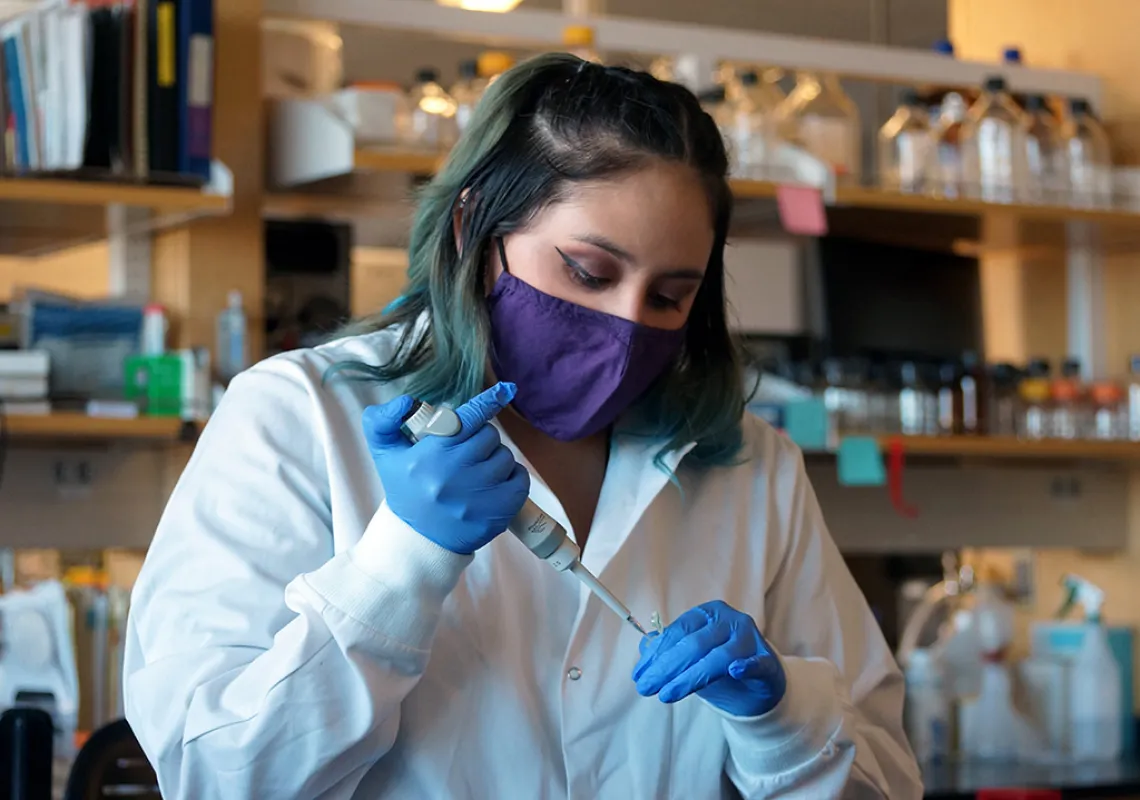

Written by Luke Wink-Moran. Photo Credit to: Luke Wink-Moran)

The first time most undergraduates try to perform a polymerase chain reaction test (PCR), they fail. Either their pipette procedure was incorrect, or their sample wasn’t sterile, or their technique was wrong. Often, it’s only after multiple attempts and multiple failures that students learn.

Catherine Vasquez, a Ph.D. student in Dr. Jil Tardiff's laboratory, studies hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy and enjoys teaching undergraduates how to perform PCR tests. She also enjoys introducing straight-A students to the idea that they will have to fail to succeed. “I think that’s the best way I’ve learned,” she explained.

Catherine’s fail-to-succeed philosophy extends beyond the lab. When she was in third grade, her family moved from Sonora, Mexico, to Nogales, AZ, where she found herself in an all-English classroom for the first time in her life. “The language barrier made school really challenging,” Catherine recalled. “I took summer classes through fifth grade just to catch up.” But despite the adversity, Catherine earned a full scholarship to the University of Arizona. “I hadn’t had the chance to take anatomy, chemistry, or physiology during high school, so I felt like I was playing catch-up for the first two years of undergrad.”

Catherine originally intended to become a physician, but she discovered that she preferred work in a research lab; the combination of flexibility, independence, and collaboration appealed to her. So she applied to UA’s masters of physiology, only to be rejected.

“It took a toll on me,” she recalled. “But my parents have always taught me to be a hard worker and to persevere. I told my mom that I was devastated when I got rejected, and she said, ‘If this is what you really want to do, then you can’t give up on it.’”

Catherine didn’t give up. She realized that one rejection didn’t define her, nor did it determine her intelligence or ability. A resume and a transcript aren’t the sum total of a student’s potential or resilience. “Rejections don’t define how good a scientist I can become,” said Catherine. So she took steps to build up her resume and reapplied to graduate school. Not only was she was accepted, but she was offered the prestigious University Fellows award, which she feels has broadened her disciplinary scope and enriched her graduate experience.

“I love the fact that I was able to meet so many Fellows, from many different disciplines, that I wouldn’t have met otherwise,” Catherine noted. “We’ve become very close, and we all care for each other and support each other. I think that’s one of the things that I was so blessed to get from the Fellows program.”

Catherine is now the first member her family to attend graduate school and hopes one day to run a lab of her own or to teach in a non-traditional classroom. She also plans to raise awareness for minorities in STEM and to collaborate with the Border Latino and American Indian Summer Exposure to Research program. BLAISER enables students to experience a lab setting and to discover the opportunities available to them in STEM. With Catherine as their mentor, the students will undoubtedly benefit from both their failures and their successes.